Dominica Roberts introduces the Spanish lady who hoped to die a martyr for the love of Catholic England

Luisa de Carvajal y Mendoza was born in 1566 into a rich, noble, and pious Spanish family. Her parents died when she was six, and she was brought up by strict but loving relations to be pious, intelligent, and charitable to the poor. Before she was twenty, she had decided that she would not marry, but neither was she called to the religious life as a nun. She spent a year in her uncle’s house, living a quiet, secluded, penitential, and prayerful life. She vowed to die as a martyr for the Catholic Church, and she felt especially drawn to Protestant England, even though her family connections made deportation more likely than martyrdom.

When she was twenty-four, her uncle and aunt died and she moved to a small house in Madrid with a friend and a few women who had been her maids. She lived on equal terms with them and sometimes under their authority. “Poverty, solitude, retirement, prayer, and penance” was her rule. She cut her hair, had the cheapest possible clothing and furniture, gave all her income to the poor, and did her share of menial tasks. Her work with the poor, including begging in the streets, was an embarrassment to her family.

Her resigning good food and sumptuous clothing in contravention with her aristocratic status made quite an impression. She vowed obedience to the Jesuit fathers in Madrid, from whom she learnt of the heroic deaths in England of St. Edmund Campion and St. Henry Walpole. In spite of her frequent illness and depression, she was increasingly convinced that she was called to go and work in England.

In 1604 King James I made a treaty with King Philip of Spain, and Luisa won a protracted lawsuit about her inheritance. She made over the whole income from her inheritance to trustees for the English Jesuit novitiate in Belgium, who used it to found St. John’s Seminary in Louvain. The first novice was Thomas Garnet, who was eventually martyred at Tyburn in 1608.

Aged 39, she set off to England with a chaplain and two menservants, accompanying a married couple, strangers to her. She took only enough money for the journey. She ostentatiously wore a crucifix and a large rosary as she rode a mule through hostile territory, not perhaps considering that her companions might not be as eager as herself for martyrdom. But she arrived safely in St. Omer after a hard journey and stayed a month with the Jesuits there.

As Lady Georgiana Fullerton (who wrote Luisa’s life in 1873) says, the English Jesuits “on account of her high rank, her well-known name and connections, as well as the weakness of her health, her ignorance of the language and want of knowledge of the country, rather apprehended her arrival.” As well they might, considering the extraordinary lack of common sense involved. But the Jesuit Provincial in England Fr. Henry Garnett sent her an escort on hearing from the Spanish Jesuits how holy she was, and after a difficult channel crossing she finally arrived in England in May 1605, with impeccably bad timing, just before the Gunpowder plot.

She spent a month in the country in a Catholic household, which broke up in a hurry just before pursuivants arrived. Catholics in London became increasingly frightened to have a Spanish guest, even though an invalid staying in her room and struggling to learn the English language. Fortunately the new Spanish ambassador had shared acquaintances with Luisa’s family and his chaplain was a saintly priest who gave up his own apartments in the Embassy to Luisa. Here, with two English girls, she spent a year in prayer and penance, though she seems to have visited Catholics in prison and elsewhere. The ambassador and his chaplain urged her to go home, but she was certain that God wanted her to stay in England. Pope Paul V expressed approval of her piety and courage,and told her to continue. She and her English companions took up a poor house near the Spanish Embassy.

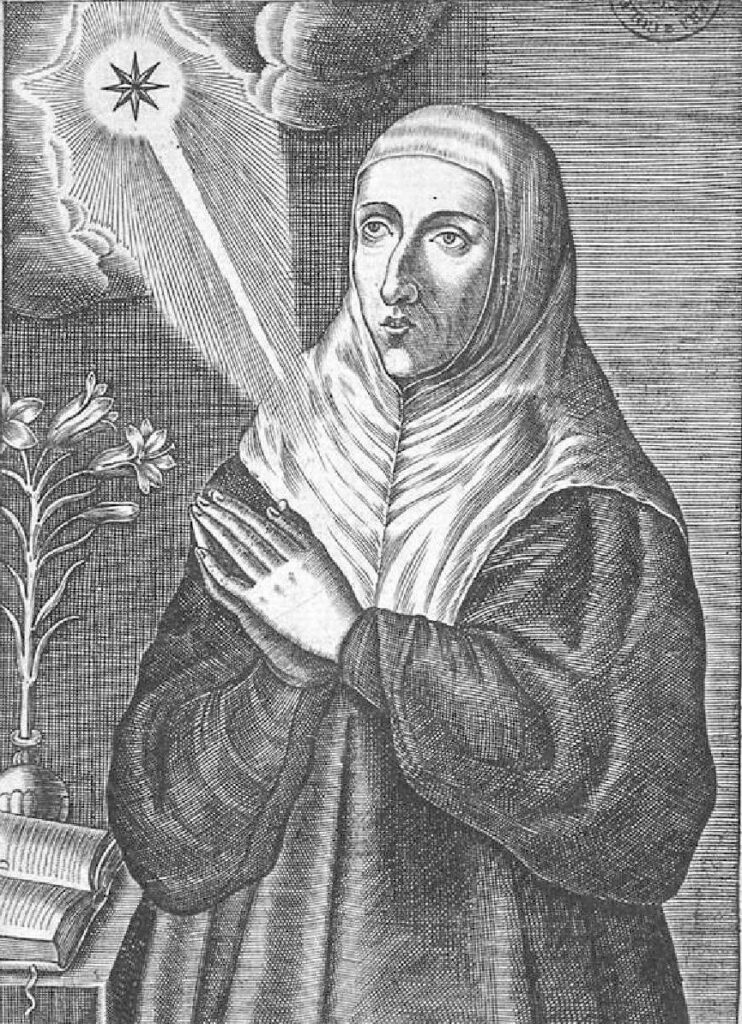

Biblioteca Nacional de España

She did have considerable success in stiffening the resolve of Catholics who were tempted to conform outwardly. The Jesuits praised her good example in this. She succeeded in persuading first the Spanish and then three other Catholic ambassadors to keep the Blessed Sacrament at all times in their Embassy chapels.

With difficulty, she had learnt enough English to argue with Protestants, and to urge Catholics back to the faith, which she did at every opportunity. In spite of mockery and insults, she knelt and prayed by a cross which still remained on a public building. She bought anti-Catholic pictures and writings when she saw them in shops, and tore them up as she walked in the street, until her confessor forbade it as attracting unhelpful notice. In May 1608 she and two companions were sent to prison, after causing a disturbance by an argument in a shop and later in the street. The Spanish ambassador secured her release and wanted to send her home, but she refused. King Philip III of Spain gave her a monthly pension via the Embassy, and some of her rich relations gave her money, with which she assisted many, especially imprisoned priests and laity. She helped and paid for men to go abroad to study for the priesthood. She bought and lent religious books, which were expensive but greatly needed. She wrote much religious mystical poetry, and publicised through her influential connections abroad the sufferings of English Catholics for the faith. A series of young girls lived with her for a time, and many became nuns, or governesses in English households.

She moved to Spitalfields, near the Flemish Embassy, to avoid the plague, and lived there for two years with companions, protected by stout doors and a fierce watchdog, while the protestant Archbishop of Canterbury became increasingly enraged by her activities and tried hard to get rid of her. Eventually, on October 28th 1613 before dawn, he sent a large force under the Sheriff of London to break in, on the grounds that it was a convent and thus illegal. They were surprised at the poverty of the household.

Luisa was worried because a priest, who had come to hear the confessions of some local women would of course be taken and condemned if recognised. Fortunately the Flemish ambassador heard the commotion and arrived, quick-wittedly implied the man was his own servant, and angrily sent him away. Luisa and three of the girls with her were sent to prison separately and were kept there for four days under very bad conditions, until the wives of the Spanish and Flemish ambassadors visited her. She was taken to the Spanish Embassy pending banishment and her companions were also freed after a few days. King Philip ordered her to be sent to his sister in Flanders, but she became severely ill owing to her recent imprisonment. She received the Last Sacraments and died in the Embassy on January 2nd 1614, her forty-ninth birthday. Her funeral was held there and her body taken to Spain. Cures were attributed to her relics, and the Spanish royal family started a process to have her canonised for her heroic virtues. Although it petered out, Luisa ought to be better known as an extraordinary heroine of this era in English Catholic history. Luisa de Carvajal, pray for us!

Article first published in Dowry No55, Autumn 2022

Cover Image: The Life and Writings of Luisa de Carvajal y Mendoza, edited by Anne J. Cruz, University of Chicago Press.