Introduction: What Crown?

What is a crown? A crown is a circle of metal, normally precious, set around the head of a human ruler. As a piece of jewellery, the crown draws attention to the head of its bearer, and more specifically to his brow, under which his brain is the organ associated with intellect and will. The crown therefore signals human authority. In the beginning, God had granted the first man authority over the material world. We read in Genesis that God had generously empowered Adam and Eve as regents of the material world: And God blessed them, saying: Increase and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it, and rule over the fishes of the sea, and the fowls of the air, and all living creatures that move upon the earth (Gen 1:28). Thus, Adam was to subdue the world and to rule over it all.

Adam did not wear a material crown as God’s appointed ruler over the material world. But he bore a spiritual crown made of the preternatural gifts. Those were qualities added to his human nature alongside justice: bodily immortality, integrity and infused knowledge. Later on, tempted by the devil, Adam ambitioned to be like God: it was the first sin. It consisted in claiming authority as his own instead of confessing it as a gift undeservedly received from God. Through sin, Adam lost his spiritual crown. His disobedience undermined his authority over the world instead of magnifying it. Just as Adam had rebelled against God, so would the material world rebel against Adam. God described Adam’s punishment: Cursed is the earth in thy work: with labour and toil shalt thou eat thereof all the days of thy life. Thorns and thistles shall it bring forth to thee (Gen 3:17-18). Thorns bear no fruit and hinder cultivation because their sharp ends scratch human skin, causing pain and bleeding. Thorns are to soil what sins are to the soul. As a sign given by God, thorns therefore manifest in botanical form the harmful consequences of man’s disobedience, all stemming from the pride once instilled in him by Satan.

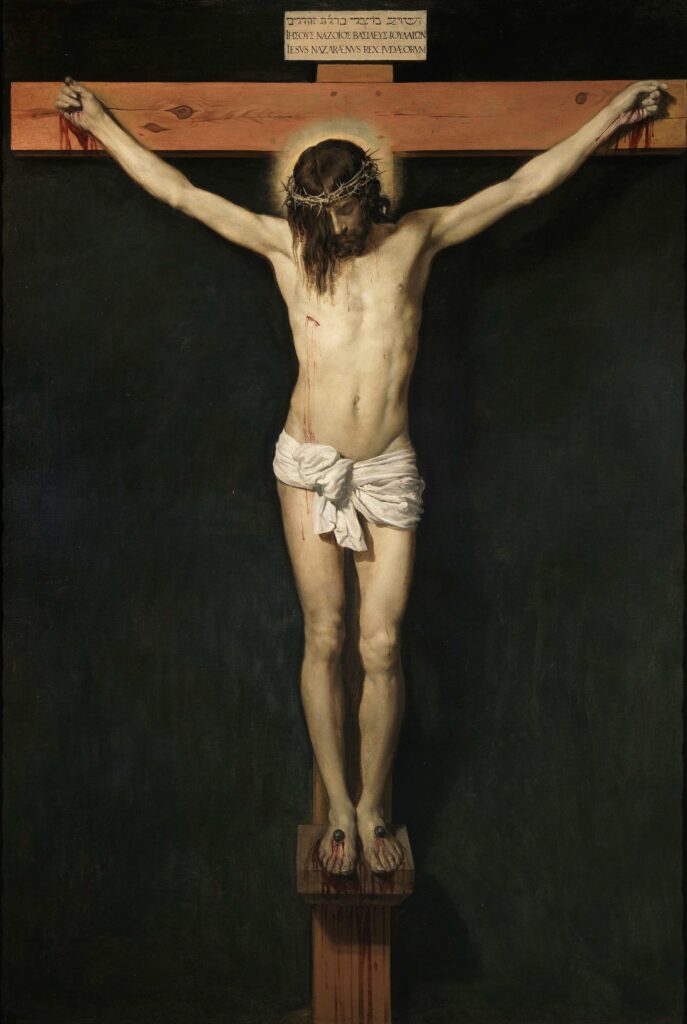

In Jesus the New Adam, God became man, dying for our sins: it wrought our redemption. In reparation for Adam’s usurpation of authority, Christ the New Adam was crowned with thorns: And platting a crown of thorns, they put it upon his head, and a reed in his right hand. And bowing the knee before him, they mocked him, saying: Hail, king of the Jews (Mt 27:29). Thorns were brought forth by the earth as a consequence of Adam’s usurpation of authority when he ate the forbidden fruit from the tree. Later on upon the Cross, again thorns encircled the brow of the New Adam above whose head a title read, Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews. The Lord Jesus, who truly was king over the entire world, accepted to be mocked in expiation of Adam’s pride. Since the crown is a symbol of sovereignty, and since pride was the main sin of Adam, the crowning with thorns synthetises our fall and our redemption. The crowning with thorns depicts sovereignty usurped: culpably by Adam, purportedly by Jesus. The moral humiliation and physical sufferings of the crowning with thorns undergone by the New Adam heal the wounds inflicted upon human nature by devilish pride since Adam of old. Our Lord suffered many torments during his Passion: sweat of blood in Gethsemane, blows and binding of limbs from his arrest onward, scourging at the pillar, carrying of the cross and finally crucifixion. The crowning with thorns is the apex of all these sufferings because by mocking Christ’s genuine kingship, it atones for Adam’s usurped sovereignty. Therefore, the crowning with thorns can be seen as the nexus of our redemption. Since the Passion of the Lord is the Hour toward which all history converges, most of its aspects were prefigured in the Old Testament. This certainly applies to the crowning with thorns. Like all events in the life of the Saviour, but supremely for the reasons just explained, the crowning with thorns is hinted at, sketched, announced, echoed in various ways in the Holy Bible. Such stages vary in precision. Some are strikingly explicit, casting meaning upon less obvious ones. Let us now examine successively: Adam and Eve’s hiding; Isaac’s ram; Moses’ bush; the Ark of Covenant; Samson’s demise; and finally Absalom’s death. We will see how those six biblical episodes display across time the pattern of a lethal entanglement of one’s head or person in wood, ultimately unfolded in the mystery of Christ’s crowning with thorns. Like shades of light separated through a prism, those six stages evoke different titles of Our Lord: New Adam, Lamb of God, Son of Man, Deliverer, Nazarene, and Son of David. On Golgotha, all titles combine like coloured waves emanating from Our Lord crowned with thorns on the throne of our redemption, the cross.

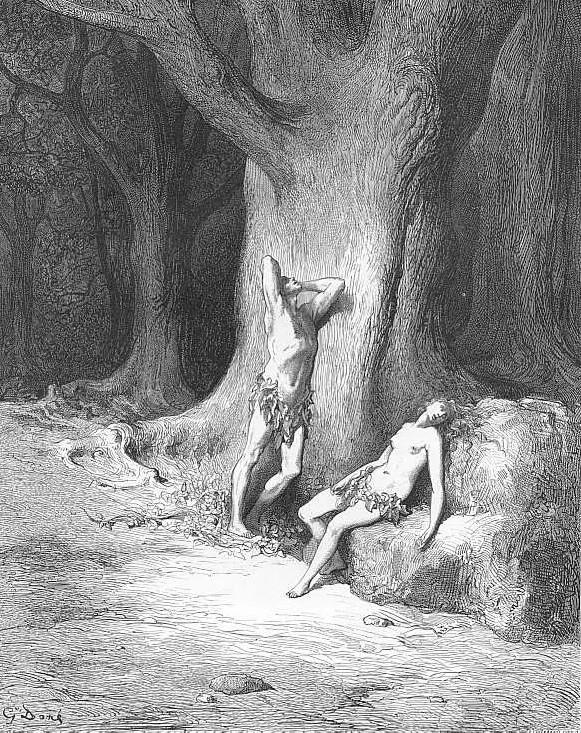

Hiding in the wood

After they ate of the forbidden fruit, Adam and his wife hid themselves from the face of the Lord God, amidst the trees of paradise (Gen 3:8). Culpably, our first parents sought concealment in some arboreal surround. The Douai-Rheims version has our first parents hide amidst trees, at the plural. Thus, they ran into a grove. However, following the Septuagint (i.e. the original Greek version), St Jerome’s Latin Vulgate translates tree in the singular, not in the plural: Adam and Eve hid in the midst of the tree of the paradise. Tree is here used collectively, and can also mean wood as a matter rather than a plant. One may even picture our first parents entering inside the tree, as if literally hiding within a wooden cavity. The conclusion is the same: whether amidst a grove or inside a hollow trunk, Adam and Eve hid in some arboreal surround. They had anticipated that gesture when, perceiving themselves to be naked immediately after eating of the fruit, they sewed together fig leaves, and made themselves aprons (Gen 3:7). Fig leaves were chosen as wider and thus more effective to cover their bodies, even though the actual trees in which they hid soon after may not have been fig trees. Let us take note of the common nature and purpose of leaves and wood, though: they belong together as the lesser and main parts of any tree, and are meant by the offenders as hiding devices. This prefigures the unity, many centuries later, between the timber of the cross and the crown of thorns of the Lord Jesus, as if the latter were branches stemming from the former. Combined, they stand as wood wherein Our Lord is caught. Thus, Adam and Eve’s posture is the initial stage in our prophetic thread of the lethal entanglement of one’s head or person in wood. Indeed both culprits are soon arraigned and death sentence is pronounced. But their progeny will avenge them, God promises: the New Adam Our Lord.

Isaac’s ram

On Mount Moriah (located in what became Jerusalem according to tradition), God instructed Abraham to spare his son Isaac. In response, Abraham lifted up his eyes, and saw behind his back a ram amongst the briers sticking fast by the horns, which he took and offered for a holocaust instead of his son (Gen 22:13). Here the pattern becomes more precise. Young Isaac was under immediate threat since, bound upon the wood of sacrifice, he could see his father’s dagger about to cut his throat. His salvation is granted by God as a reward for the obedience of Abraham (and his own). This fortunate outcome is sealed by a sacrifice of substitution. An animal is killed instead of the son. What we should note at this stage is the posture of the victim. The ram is caught in brambles by the horns, therefore, by its head. Instead, the animal could have been caught by its leg in a crevice, the landscape being mountainous. Like sheep, rams naturally grow long tails swelling with fat, when not cut off by shepherds as would have been the case for a wild ram in the desert mountain of Moriah. The ram’s wide and long tail then could have plausibly caught in brambles. Or else, the ram could have been caught by its neck. Or simply, it could have been wandering unawares and directly seized by Abraham, well accustomed to such handling, since he had sheep and oxen and he asses (Gen 12:16). All those suppositions help us realise that the posture of the ram conveys prophetic meaning. With its horns entangled, that is, its head, the ram mirrors Isaac bound on the wood and announces the definitive Victim, the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world: Christ crowned with thorns, that is, also caught by the head in brambles.

Moses’ bush

This third episode is similar to that of Isaac’s sacrifice. In both instances a nomadic shepherd (Abraham, Moses) travels toward a mountain (Moriah, Horeb) where God speaks to him in close connection with a bush: Now Moses… drove the flock to the inner parts of the desert, and came to the mountain of God, Horeb. And the Lord appeared to him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush (Ex 3:1-2). The Hebrew word used is seneh, a thorny bush, perhaps a blackberry bush. The Greek word is batos (βάτος): a thorn bush or bramble bush. We can be sure that the bush had thorns because the same word was used by Our Lord when referring to Moses’ bush: Moses also shewed, at the bush, when he called the Lord (Lk 20:37); and in his comparison of the good and bad trees: For men do not gather figs from thorns; nor from a bramble bush do they gather the grape (Lk 6:44). Unlike in Isaac’s story though, here no threat weighs upon either boy or ram. Could it be that God be the one made vulnerable through dwelling in the bush? Is God caught in the brambles? No mention of a head is needed here, God being incorporeal. But the Fathers of the Church have interpreted the Burning Bush as a prophecy of the Incarnation of the Divine Word. The fire is the godhead, they wrote, and the unburnt bush is the human nature assumed yet not consumed. Some authors are more specific, suggesting that the fire is Our Lord yet unborn and the bush is Our Lady pregnant, whose virginity, like the shrub, is brightened, not consumed, by the divine Fruit she bears. Further, it could prefigure the Holy Eucharist in which the divine Presence communicates itself through the externals of wine and bread. When becoming Jesus Christ, therefore, the Word eternal entangled himself in our human nature out of love, like the fire in the thornbush. He became our substitutive victim like the ram caught in Abraham’s bush was for Isaac. As the biological progeny of Mary, Jesus is therefore truly the Son of Man, subjected to death that we may rise.

The Ark of the Covenant

Once Moses had led the Hebrews out of Egypt God commanded him to build the Ark of Covenant: a piece of sacred furniture the size of a chest. Within it the Almighty would dwell, accompanying his people on their way to the Promised Land: Frame an ark of setim wood… And thou shalt overlay it with the purest gold, within and without; and over it thou shalt make a golden crown round about (Ex 25:10-11). After Adam and Eve’s hiding tree, Isaac-ram’s thicket and Moses’ burning bush, once again we encounter the pattern of a presence caught within wood. As with the burning bush above, no head of the incorporeal God needs mentioning here, or obliquely through the faces of his two angels carved on the top of the ark. The Hebrew word setim (or shittim) means acacia. The Vulgate explains it as not liable to putrefaction. The Hebrews came across acacia trees when wandering in the desert. To survive heat, acacias grow very dense, strong wood, hence unpalatable to insects or other decay agents. The surround pattern occurs again with the golden crown round about the ark. The Septuagint reads: You shall make [for] it a waved border of gold, twisted round about. Thus, once again God assigns the pattern of wooden encirclement (here with acacia enhanced by gold) as a sign for his presence, either personal or prophetic. In addition, most acacia trees grow thorns, some up to three inches long (over seven centimetres). Thorns were surely cut off for the wood to be shaped into an ark, but the notion of threat is by no means absent from this sacred device since thousands of Philistines were killed by God for having captured his ark (1 Sam 5; 6). Indeed, the ark inspired dread down to King David’s time. On its way to Jerusalem, the guard Oza put forth his hand to the ark of God, and took hold of it: because the oxen kicked and made it lean aside. And the indignation of the Lord was enkindled against Oza, and he struck him for his rashness: and he died there before the ark of God (2 Sam 6:6-7). Its sacredness kept hands off the ark more surely than its original acacia thorns shaved off. God further commanded: Thou shalt put in the ark the testimony which I will give thee (Exo 25:16). The Septuagint mentions here testimonies in the plural, martyria (μαρτύρια). They are the stone tablets of the law, Aaron’s rod and a jar of manna. Historically connected with Moses, all three items point to Christ as the definitive Deliverer: Giver of the New Law, Saviour through his Cross and Bread of Angels.

Samson’s demise

An ambivalent character listed among the judges of Israel, Samson also prefigures Christ in striking ways: notably through his treacherous delivery for money, his bringing the wooden gates of the city up to a nearby hill like Christ carrying his cross to Golgotha, and his sacrificial death. Intending to betray Samson to his enemies the Philistines, his ill-trusted Delilah presses him to reveal the secret of his superhuman strength. He deludes her twice, pretending that binding him with cords and ropes would overcome him. His third riddle leads her dangerously close to the truth, pointing to his head and hairs instead of man-made bonds: If thou plattest the seven locks of my head with a lace, and tying them round about a nail, fastenest it in the ground, I shall be weak (Judg 16:13). Her attempted betrayal having failed a third time, Delilah allows Samson no respite so that, His soul fainted away, and was wearied even unto death (Judg 16:16). His anguish announces that of Christ in Gethsemane, My soul is sorrowful even unto death (Mk 14:34), sorrowing upon the fallen human race, the unfaithful spouse whom he comes to cleanse in his blood. Samson finally gives up and admits to Delilah: The razor hath never come upon my head, for I am a Nazarite, that is to say, consecrated to God from my mother’s womb: If my head be shaven, my strength shall depart from me, and I shall become weak (Judg 16:17). The Lord Jesus was called a Nazarene, not only because he grew up in Nazareth but because he was consecrated to God even from conception, better than Samson or any prophets. Nazarites were to wear long hair, as echoed in all traditional depictions of Our Lord from his Holy Shroud onward. Paradoxically, Samson was safe when his hairs were entangled in lace and tied around a nail; whereas he was doomed once shaven. This prefigures Jesus’ entanglement of love when crowned with thorns. Christ vanquished as the thorns combed his long hair, piercing his scalp. Upon the tree of the cross, quoting the psalm where his sufferings were prophesied in striking details, the true Nazarene affirmed his total consecration to God: From my mother’s womb thou art my God (Ps 21:11).

No thorns or brambles caught Samson, even though he lost his eyes when betrayed. Our thread of the arboreal entanglement seems interrupted here. Still, his posture implied a lethal embrace as Delilah craftily lulled the lover she has already sold for money: She made him sleep upon her knees, and lay his head in her bosom (Judg 16:19). Prophetically, would not that sentence describe just as fittingly the newborn Child Jesus in his young mother’s arms, and even the dead Christ embraced by his sorrowful mother the Blessed Virgin Mary? For us who came long after Samson and Delilah, their embrace gleams like an evil negative of the Nativity or of the Pietà. The crowning with thorns fulfils, we realise, the entanglement of love initiated at the Incarnation and manifested at the Nativity. As the sacred liturgy affirms, Beata viscera Mariae Virginis quae portaverunt aeterni Patris Filium: Blessed is the womb of the Virgin Mary, that bore the son of the everlasting Father. Our contrition increases and our gratitude even more when devoutly recalling the virginal viscera after the Latin quote above. The Virgin’s bowels, to translate literally, form the organic entanglement sought by the Word Eternal when becoming man in Our Lady’s womb. To what end? To die on the cross for our sins, his kingly head entangled in brambles. It was still a plant, then, in which the incorporeal Word was caught through his Incarnation, the Jesse Tree of his human descent, culminating in Jesus the divine Nazarene, that is, following St Matthew’s connection with the word nezer, an offshoot.

Absalom’s death

The name of King David’s third son was Father of Peace, from Abba, father, and shalom, peace. The similitudes between Absalom and Our Lord are more numerous and striking than with Samson, as are the contrasts. Absalom intrigued to succeed his father before the time, even waging war against him. Jesus came to do his Father’s will, even unto death. Absalom’s external appearance was unrivalled: But in all Israel there was not a man so comely, and so exceedingly beautiful as Absalom (2 Sam 14:25). Not of his rebellious son, though, but of the divine Messiah did King David prophesy: Thou art beautiful above the sons of men: grace is poured abroad in thy lips; therefore hath God blessed thee for ever (Ps 45:2). Samuel wrote further of Absalom that, From the sole of the foot to the crown of his head there was no blemish in him. Contrasting word for word, Isaiah beheld Christ in his Passion: From the sole of the foot unto the top of the head, there is no soundness therein: wounds and bruises and swelling sores (Isa 1:6).

The circumstances of their deaths bring our thread of the lethal wood entanglement to its climax. Both sons of David rode on a mule soon before being caught, their heads entangled with branches: As [Absalom’s] mule went under a thick and large oak, his head stuck in the oak: and while he hung between the heaven and he earth, the mule on which he rode passed on. And one saw this and told Joab, saying: I saw Absalom hanging upon an oak (2 Sam 18:9-10). After the Resurrection, St. Peter bore witness before the Jews to Jesus, whom you put to death, hanging him upon a tree (Acts 5:30). All four evangelists affirm of Jesus that, platting a crown of thorns, they put it upon his head (Mk 15:17). Vital force emanated from Absalom, but purely material and probably vain. Thus he had been described earlier as growing hair in striking quantity: When he polled his hair (now he was polled once a year, because his hair was burdensome to him) he weighed the hair of his head at two hundred sicles, according to the common weight (2Sa 14:26). In contrasted similitude, St. Luke wrote of Jesus that, all the multitude sought to touch him: for virtue went out from him and healed all (6:19). It is likely that Absalom’s abundant mane caught all the more tightly into the branches of the oak, sealing his fate as Joab, took three lances in his hand, and thrust them into the heart of Absalom (2 Sam 18:14). Following the Hebrew, the Greek Septuagint brings together the heart of the fugitive son and, surprisingly, the heart of the oak tree: Jonas stuck the arrows in the heart of Absalom [while] yet he was living, in the heart of the oak. Indeed the same Greek noun cardia, heart, is used for the man (καρδία Αβεσαλώμ) andfor the tree (καρδία τῆς ὃρυός). The oak thus appears as an extension of the man. Their hearts superimpose as his hair mingles with its branches. This detail strengthens the assimilation of the human victim with the arboreal creature. Their association seems fortuitous in this episode of the Old Testament, but not in the light of Jesus’ crucifixion and crowning with thorns. According to his revelation, God intended a correspondence between Christ, fruit of our redemption, and the cross, tree of salvation. A bitter summary of mankind’s aversion from God, the palms waved by the crowd in acclamation before the Son of David entering Jerusalem on his mule became, but five days later, lethal thorns forced around his head. Such a mystery could not be explained all at once. Its unfolding was prepared by stages.

Conclusion: Harvesting

We have just surveyed various episodes of sacred history as if flying over a dense forest. The intricate complexity of so many details and concrete circumstances can overwhelm us, making us wonder where this is all leading up to. Are we lost? Through one pin on the map of redemption―the holy Cross planted on Golgotha―God solves our helplessness. To the Cross of his Son everything leads, and from it all life stems. The Cross is steady while the world turns, to quote the motto of the Carthusians: Stat crux dum volvitur orbis. Falling from grace, Adam was expelled from Eden. God followed him headlong, moved by compassion. Adam was caught in the wood, a symbol for his godless outlook on creation. So God got himself caught in the wood as well. How? Prophetically, through victimal substitution with the ram caught by the head in the thicket. Through arboreal illumination in the burning bush. Through wood wrapping in the wandering Ark of Covenant. Through organic nesting in the Virgin’s womb as prophesied in Samson’s head caught in Delilah’s bosom. Finally, through the actual hanging of Absalom’s head from the tree.

The transformative power of divine grace is such that God, made wood for the sake of rescuing Adam, revives fallen humans through grafting them in him. Thus, St. Paul applies that horticultural verb to Jews and Gentiles alike: And they also, if they abide not still in unbelief, shall be grafted in: for God is able to graft them in again (Rom 11:23). Such spiritual grafting occurs when we embrace the true faith. But any living branch requires sap. The sap of our souls is the Holy Eucharist, flowing in us through Holy Communion. In that main sacrament the fall of Adam is fully repaired. Lured into the tree by the serpent in Genesis, Adam had turned away from God, eating of the tree or wood, hence losing the godly use of his reason. Having embraced a tree against God’s order, Adam had spiritually become wood himself as is the fate of idolaters: Let them that make them become like unto them: and all such as trust in them (Ps 115:8). As a merciful antidote, the New Adam made himself vine to pour the sap of his own blood into our bodies and souls.

We can now better appreciate the divine logic illustrated by the various stages described earlier. God had made himself wood, that is, he had manifested or prophesied his presence through botanical surrounds to reach us where we lay, rooting us and grafting us back in him to unite us with him anew. The clusters of grapes and sheaves of wheat carved on the tabernacles of our churches fittingly display this literal transformation of plants by God into his Body and Blood for our consumption and salvation. Which of us would not want to be crowned in his turn with such Eucharistic wreaths, helmets of salvation purchased for us by the Lord? After the grapes and wheat changed into the Eucharistic Body and Blood of the Lamb, our persons are turned into his limbs, mystically.

But again, all the merit of such a salutary change stems from the racking of the Lord upon the tree of the Cross and the piercing of his kingly brow within the fiery crown of thorns. Glory to the King who redeemed us from the barbed jungle of sin at the cost of his divine sap: Christus vincit! Christus regnat! Christus imperat! Christ conquers! Christ reigns! Christ commands!

Article first published in Dowry 57

Cover Image: Christ Crowned with Thorns by Caravaggio (1602-1604, Public Domain)